Dr. Ali E. Abbas, Ph.D., is a Professor at the University of Southern California (USC), specializing in Industrial and Systems Engineering and Public Policy. With his profound expertise in these fields, he has pushed the boundaries of decision-making and ethics. At USC, Dr. Abbas has taken on various pivotal roles, including positions within the School of Public Policy, demonstrating his interdisciplinary approach to academia.

Dr. Abbas is widely recognized for his scholarly pursuits in the fields of decision making and ethics. He has authored and co-authored numerous influential research papers and books, firmly establishing himself as a prominent figure in the fields of decision analysis and ethical decision making. Some of his noteworthy works include “Foundations of Decision Analysis,” which he co-authored with Ronald A. Howard. Additionally, he has made significant contributions through publications such as “Foundations of Multiattribute Utility,” “Next-Generation Ethics,” “Improving Homeland Security Decisions,” and “Ethical Decision Quality: Building an Ethical Decision Culture.”

He has received widespread acclaim for his outstanding contributions, earning multiple accolades from the National Science Foundation. His research papers have secured prestigious first-place awards with the INFORMS Decision Analysis Society, while his work on applying Utility Theory in Engineering Design, published in the esteemed IEEE Systems journal, has garnered significant recognition.

In addition to his academic pursuits, Dr. Abbas is deeply committed to community engagement and education. He devotes his time to equipping underserved youth in Juvenile Detention Centers with essential decision-making skills. Furthermore, he has spearheaded the creation of a social network dedicated to promoting these invaluable skills. Driven by his unwavering dedication, he actively bridges the gap between academia and practical applications, as exemplified by his co-chairing of an innovative conference between the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) and the university.

Dr. Abbas has shared his thought-provoking perspectives on a diverse range of topics, demonstrating his expertise through his contributions to opinion pieces on CNN and his appearances in television interviews. His recent feature in ISE Magazine, delving into the systems perspective of crime, highlights his unwavering dedication to advancing knowledge and fostering practical solutions within the field.

The following interview follows a presentation jointly hosted by the Society of Decision Professionals and the Decision Analysis Society of INFORMS about his new book:

Ethical Decision Quality (EDQ): Building an Ethical Decision Culture.

The interview addresses fundamental questions about ethical decision-making on an organizational level.

In your presentation, YouTube: https://youtu.be/N9ADhDq-STI you mentioned the challenges of defining an unethical act. Can you elaborate on why deception, harming, and stealing are the focal points and how these factors contribute to ethical decision quality concerns?

Certainly, deception, harming, and stealing are fundamental ethical concerns that commonly arise in decision-making. They were present in most of the ethical collapses I have examined. These elements encapsulate actions that deviate from high moral standards and can have severe consequences.

The efficacy of ethics courses has been questioned in recent articles. Can you share your perspective on whether business schools can effectively teach students to be virtuous decision-makers, considering the prevalence of ethical collapses?

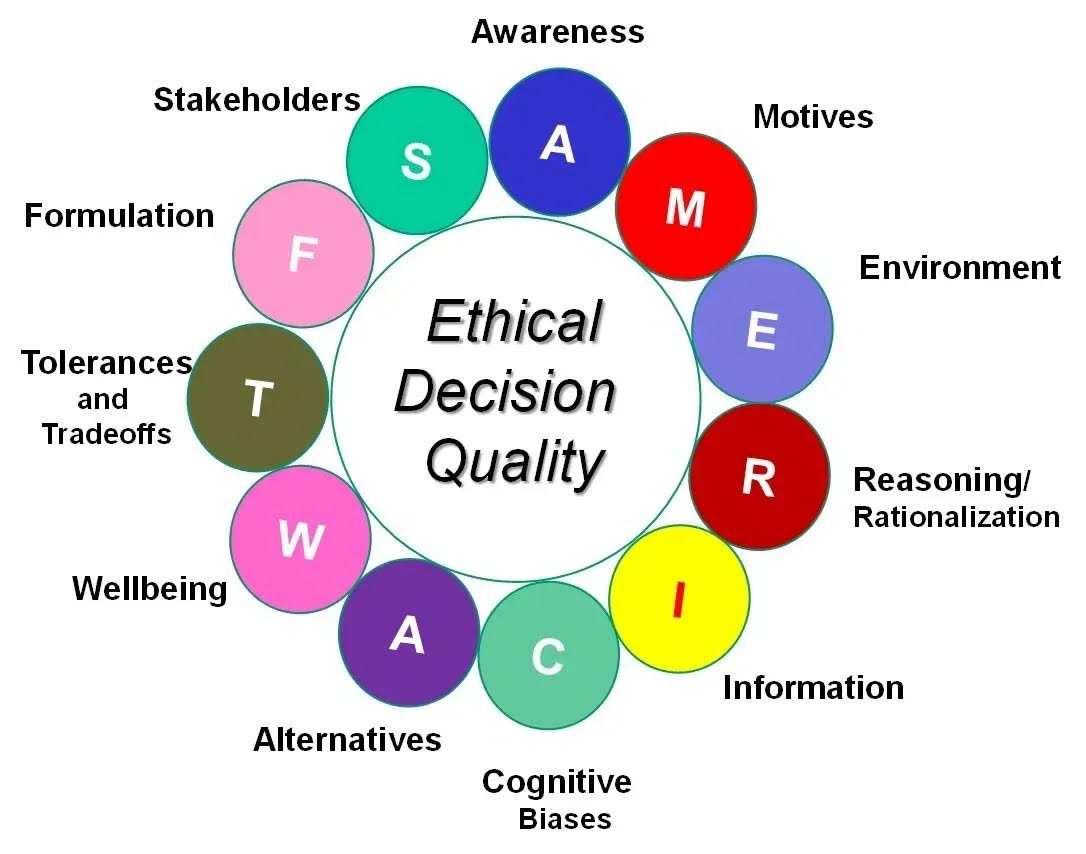

It’s a valid concern that was raised by the WSJ and the New York Times. While ethics courses play a crucial role, they might not be sufficient on their own. In my book, I introduce 11 elements known as the Elements of Ethical Decision Quality (EDQ) that can help assess the ethical quality of a decision. I also provide six organizational mindsets that were leading causes of ethical collapses.

You touched on the potential impediments to incorporating ethical decision quality in organizations. Could you elaborate on common challenges faced in this regard and any solutions you might propose?

Common challenges include the confusion between ethics and compliance, as well as the misconception that having integrity in core values guarantees ethical decisions. Solutions involve fostering a deeper understanding of ethics, understanding the mindsets, emphasizing a proactive approach to ethical decision-making, and encouraging a culture that values ethical considerations alongside compliance. This is what I call “Building an Ethical Decision Culture”

How should decision analysts guide clients through ethical dilemmas, where there are no “pure” options and they must weigh who will be harmed and to what degree?

The tools of Decision Analysis are by themselves amoral, but there is a lot that can be done to address ethical dilemmas with an emphasis on Ethical Decision Quality (EDQ). In particular, going through an assessment of the elements of EDQ when faced with an ethical dilemma. Here are some examples (Chapters 8 – 18 talk in more depth about specific action items in relation to the elements of EDQ):

- Ethical Awareness is the first element of EDQ that helps make sure that everybody is on board with what comprise an unethical act.

- Ethical tolerances and trade-offs are a second element. Getting clarity on the ethical tolerance that an organization is willing to operate with, and the ethical trade-offs (when there is a benefit to the organization vs. other stakeholders). Knowing these elements and what you will (or will not) do also helps mitigate the escalation of ethical issues when a situation arises.

- Decision Analysis can draw on a wealth of expertise and practice generating better alternatives. With EDQ, the focus will also be on generating ethical decision alternatives that may themselves resolve or bring clarity on the dilemma or even provide less harm to others.

- Incorporating uncertainty into the analysis can help anticipate/avoid unintended consequences and brainstorm follow-up actions. Incorporating uncertainty also allows room for assessing the credibility of information using normative methods. We hear quite often that many people have spent years in prison only to have their conviction overturned years later.

- Cognitive biases can help understand/mitigate peoples’ reactions in certain ethical issues with ethical implications e.g. group think, obedience to authority biases, ad many others.

- Understanding the environment, the incentive structures, and their ethical implications can also help avoid ethical issues.

- Understanding the reasoning that is used in making a decision is important in addressing concerns. For example, is an organization going to rationalize with a Kantian vice utilitarian perspective? Will it incorporate all the information and preferences into a meaningful decision-making system? And will it understand common rationalizations that enable unethical decision verdicts?

How does courage factor into your findings?

Courage affects an individual’s willingness to stand up to acts of deception, harming and stealing when they see them. The opposite is fear, where individuals are much more willing to tolerate these acts. This is part of an element of EDQ called well-being (Chapter 14).

A quote by Bertran Russel mentions “Neither a man nor a crowd nor a nation can be trusted to act humanely or to think sanely under the influence of a great fear.”

Building on individuals’ actions in fear, many tactics have been introduced. According to Wikipedia, fear mongering, or scaremongering, is a form of manipulation that causes fear by using exaggerated rumors of impending danger. Fear mongering is routinely used in psychological warfare to influence a target population.

Some organizations even try to create an atmosphere of intimidation for the purpose of suppressing moral courage. As I mention in the book, Mike Coates, a former HSBC employee who worked on financial crime compliance and left the bank in 2018, said the industry’s profit-focused incentive structures can still override the fight against financial crime. “You can’t get a man to believe in something when a salary depends on him not believing it,” said Coates.

How is EDQ part of the lawyer’s remit? Would a client really want that? Isn’t a lawyer’s job to advance the interest of his/her client within the bounds of the law?

This is an important question. It is indeed the job of a lawyer to help an organization navigate the legal system and take advantage of some of its benefits. The question is whether an organization would like to navigate the legal system, take advantage of its privileges and be ethical along the way.

When an organization posts “integrity” in its core values, it never says “integrity within the legal domain”, rather it just says integrity. So this is a reality test.

Now if the purpose of being ethical by itself is not a reason, another reason for an organization to adopt this is that many times the legal team can get it wrong. Many of the organizations presented in Part 1 of the book received advice from a legal team.

Enron’s Skilling said in a televised interview, “Arthur Andersen and our lawyers had taken a very hard look at this structure, and they deemed it appropriate.” The follow-up: Skilling was initially sentenced to twenty-four years in prison.

Examples abide. The Air & Waste Management Association reported in its EM Magazine in June 2018 about Volkswagen: “It is impossible for us to know exactly what legal advice VW received (Thank you, attorney-client privilege . . .), but it is interesting to speculate whether VW’s internal response would have been different if outside legal counsel had simply said “there is no analog for this, it’s uncharted territory” or “here’s the worst thing we found, given our different facts, we could easily be facing penalties ten times greater (i.e., US$1 billion-plus).” The follow-up: billion-dollar fines and jail time.

As I mentioned in my book the legal system often takes time to catch up :” The LA Times reported about a change in the legal system in California, “California attorneys must report misconduct by their peers.” Further, the State Supreme Court now obligates attorneys to notify the State Bar if they have “credible evidence that another lawyer has committed a criminal act or has engaged in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit” or other wrongdoing that “raises a substantial question as to that lawyer’s honesty, trustworthiness, or fitness.”

Most of the mindsets you identified are characterizations of the organization’s rationalizations/cover-up once they are caught and subjected to public scandal (lagging indicators); are there leading indicators?

Great question. Some of the mindsets e.g. “Unethically Fast and Slow” are examples of reactions once a scandal has occurred. But there are also leading indicators:

The Legally-unethical mindset, the Pendulum Swings Mindset, the Black Hole Mindset , and Organizational Transgressions are leading indicators that occurred before the collapse. These mindsets as well as weaknesses in the elements of EDQ are the leading indicators. They were great predictors for many cases such as Enron, Madoff, Theranos, Valeant and many others.

Can the ethical quality of a decision (EDQ) be evaluated ex ante (like DQ)? Or can it only be determined from the outcome?

Yes. The ethical quality of a decision can indeed be evaluated ex ante. There is an assessment of the elements of EDQ presented in the book. This can apply to an individual or an organizational assessment. For example, the assessment would focus on motives and explore whether any of the decision-makers have personal motives that may influence the decision. The assessment of awareness would focus on the intent.

As Dr. Benjamin Franklin noted: “I doubt too whether any other Convention we can obtain may be able to make a better Constitution. For when you assemble a number of men to have the advantage of their joint wisdom, you inevitably assemble with those men all their prejudices, their passions, their errors of opinion, their local interests, and their selfish views. From such an assembly can a perfect production be expected?”

The assessment also explores the effects of the environment, and whether there are dominant features such as a band wagon, or “do whatever it takes to get the job done” or social clubs and exchange of favors or group think biases.

What thoughts do you have on how ethical lapses can influence trade-offs in decisions?

Yes, there are indeed many examples where ethical trade-offs are affected (unfortunately in an extreme way) following an ethical collapse. If an organization has a decision process, they will be less affected by the swings that occur in the trade-offs. But when they don’t, the collapse usually results in what I refer to as “Erratic Decision Making Around a Trending Bandwagon”. Sometimes organizations swing backward and forward in ethical trade-offs until it is back to normal.

I will draw on an example from personal experience as I quote from the book: “Following the oil spill incident in the Gulf, as an example, many oil, gas, and energy companies launched initiatives to improve decision-making. I was invited to give a seminar in the headquarters of a large organization, and so I decided to talk about values. I asked what values their organization cares about when making decisions. Immediately, everybody responded, “Safety.” I asked if there were any other values, and after some discussion, they said “Having a clean environment.” I asked if there were any other values, and no hands were raised. There was a pause. After about ten minutes, a participant sitting at the back of the room raised their hand hesitantly and said, “Profit.” He seemed embarrassed by saying it. “

The issue was not that they cared heavily about safety and the environment, but that they did not mention profit. It was clear the focus had shifted from profit (possibly due to internal memos and top-bottom slogans about the importance of safety and the environment). But if that is all they really cared about, then they could achieve those values (safety and environment) by shutting down all their operations. They would have a stellar safety record and have minimal impact on the environment. And when an esteemed group of executives answers this way, it would be difficult for them to make meaningful decisions that involve profit.

Building upon the concept of a universal standard of ethics, there are different cultural biases in terms of level of tolerance. Is it ethically flawed for multi-national corporation to be indifferent to these cultural differences or adjust accordingly?

This is an important question. The ethical tolerance of an organization should not depend on its geographic location or operation in different parts of the world. The ultimate question is what the organization is willing to tolerate (its ethical tolerance) in its operations anywhere in the world regardless of the legal system or the cultural norms.

While the legal system in a particular country might allow/tolerate certain things and prevent others, it will be up to the organization to have a unifying ethical tolerance.

For example, in some parts of the world, giving a bribe to a government employee to get paperwork signed and expedited is every-day practice. The ethical concerns include whether getting that permit expedited impacted other stakeholders adversely. If so, and if their ethical tolerance does not allow that, then they should not do it in any geographical location, even ones that deem that normal practice.

Likewise, is an organization willing to have child labor that work more than 14 hours per day, with no safety insurance in case of an accident due to fatigue? I mention in the book “Fatigue is another factor that impairs ethical decision-making as it impairs an individual’s ability to function and jeopardizes safety during the job” If its ethical trade-off does not allow it then it should not engage in that activity anywhere. This is not a matter of paying different wages in the U.S. or overseas but a matter of exposing individuals to deception/ harming/ stealing in some parts of the world versus others.

Is there any form of advocacy that is currently being lead to create these types of decision processes?

I hope that the word spreads and that the concept is adopted by many organizations. I am hopeful because when it came to DQ, many organizations implemented decision processes and in-house training ( e.g. Chevron, BP, Intel, and many others). Efforts like those of Society of Decision Professionals ( SDP) and the Decision Analysis Society (DAS) of INFORMS could be great starters for this initiative.

I believe that organizations need to have a focus on implementing an ethical decision culture, not just mentioning integrity in the core values without specifying ethical tolerances and trade-offs, or assessing the elements of EDQ, and then having a compliance team.

Can you comment on how the organizational behaviors impact individual decision making (example: how organizational incentives lead to unethical decision-making—Boeing 737MAX) and how that might be prevented?

Organizational behaviors influence the operating environment, the incentives, biases, and motives that impact ethical decision-making. Incentive structures are quite often incompatible with utility-maximizing alternatives. Rewards are often made based on the outcome and not the process. And many decisions are made following the path of least resistance or obedience to authority.

I note in my book that Groupthink is also a situation that arises when members of a group focus on (and strive to reach) a consensus on a decision due to pressure or conformity instead of analyzing and challenging the proposed alternatives or expressing an opposing view. The results are often disastrous, and people often wonder how such decisions could have been made. Groupthink played a role in the Challenger space shuttle disaster, where concerns about the sealing abilities of an O-ring at a particular temperature were ignored. This was cited as the main issue that led to the explosion. There was pressure on NASA to launch after surveys showing that the popularity of the Space Shuttle Program was fading.

Another incident of groupthink and obedience to authority was displayed in John F. Kennedy’s Bay of Pigs invasion decision, where he was surrounded by individuals who did not express any opposing views. Arthur Schlesinger, Kennedy advisor and historian noted: Our meetings were taking place in a curious atmosphere of assumed consensus, [and] not one spoke against it.

As noted in a Wall Street Journal article “All the President’s Yes-Men: JFK remade his decision-making process after the Bay of Pigs debacle,” the decision went through partly because nobody among JFK’s advisors was willing to speak up or play devil’s advocate. After that decision, JFK created the Executive Committee of the National Security Council, which could openly express its ideas and debate national security decisions. Further, it met with and without the president to minimize the effect of obedience to authority and the yes-man environment. Robert Kennedy later recalled, “There was no rank, and in fact, we did not even have a chairman . . . the conversations were completely uninhibited.”

Thank you, Ali, for sharing your insights and addressing these crucial aspects of ethical decision quality. We appreciate your time and expertise.

My pleasure. Thank you for the engaging discussion.

For more information:

SDP Website: https://www.decisionprofessionals.com/library/SDP-Webinar-2023—Abbas-(Ethical-Decision-Quality)

Ethical Decision Quality Website: https://ethicaldecisionquality.com